Wersja z 2013-10-12

Germanie stanowili w historycznej przeszłości zespół zbliżonych i spokrewnionych plemion indoeuropejskich, zamieszkujących głównie północną część Europy. Jak w każdym innym analogicznym przypadku, ich tożsamość etniczną budował przede wszystkim wspólny język i kultura duchowa, w mniejszym stopniu kultura materialna. Zupełnym nieporozumieniem byłoby doszukiwanie się wśród tego etnosu wspólnoty genetycznej – przyczyny tego stanu rzeczy wyjaśnione zostały w artykule o pochodzeniu Słowian. Genetyka bywa nieocenioną pomocą dla poznania dziejów ludzi w wymiarze biologicznym, jednak genealogia konkretnych ludzi nie musi mieć wiele wspólnego z językiem ani przynależnością etniczną ich przodków. Dziś germański etnos faktycznie już nie istnieje – zamiast o Germanach możemy mówić jedynie o ludach germańskich, tzn. o ludach, których języki wywodzą się z języka historycznych Germanów.

Umowny termin język germański oznacza nieznany z zapisów język, będący przodkiem wszystkich współczesnych języków germańskich (niemieckiego, holenderskiego, angielskiego, szwedzkiego itd.) tak samo jak łacina jest przodkiem wszystkich języków romańskich (rumuńskiego, sardyńskiego, włoskiego, francuskiego, prowansalskiego, katalońskiego, hiszpańskiego i portugalskiego). Istnienie tego języka uchodzi w nauce za pewne (natomiast pogląd, że język taki nie istniał, uważa się za zupełnie nieprawdopodobny). Termin język germański odpowiada angielskiemu Germanic. W tym samym lub podobnym znaczeniu używa się określeń język pragermański, prajęzyk germański lub język ogólnogermański (Common Germanic).

Wczesne dzieje Germanów znane są bardzo słabo i są często co najwyżej przedmiotem spekulacji. Wiedza starożytnych na temat Germanów była przez długi czas znikoma lub żadna, bo też zamieszkiwali oni dostatecznie daleko od terenów, na których kwitła jakakolwiek cywilizacja z umiejętnością pisma. Dopiero w roku 233 p.n.e. (zapewne germańskie) plemię Bastarnów przybywa z północy i zajmuje tereny dzisiejszej Mołdawii i delty Dunaju, dzięki czemu daje się poznać światowi cywilizacji klasycznej. Jednak jeszcze przez pewien okres, co najmniej do czasów Polibiusza (II wiek p.n.e.), Germanie wciąż są mieszani z Celtami. Ich odrębność zauważa dopiero grecki filozof i historyk Posejdonios z Apamei (lub z Rodos) w pierwszej połowie I w. p.n.e. Jeśli interpretacje jego znanych głównie z przekazów dzieł są poprawne, to właśnie on pierwszy wprowadza do świadomości ówczesnych ludzi piśmiennych nazwę Germanie. Więcej informacji o Germanach spotykamy dopiero w dziełach Gajusza Juliusza Cezara.

Pojawienie się Bastarnów (III wiek p.n.e.) to okres, gdy Germanie rozpoczynają ekspansję ze swojej praojczyzny, a germańska wspólnota językowa jest już zapewne przynajmniej częściowo rozbita. Źródła pisane niewiele zatem mogą nam powiedzieć o pochodzeniu i wczesnych dziejach tego etnosu. Pomocą jest natomiast przede wszystkim językoznawstwo, archeologia i mitologia.

Germanie byli jednym z odłamów Indoeuropejczyków, chcąc zatem prześledzić ich losy, musimy cofnąć się w czasie do okresu, gdy jednolita językowo wspólnota indoeuropejska zaczęła się rozpadać i zajmować nowe tereny.

W świetle współczesnej wiedzy najbardziej wiarygodne jest przekonanie, że indoeuropejska wspólnota językowa istniała około 4500–3500 p.n.e. na terenach stepów na północ od Morza Czarnego i Kaukazu. Udomowienie konia (używanego pierwotnie jako zwierzę pociągowe), opanowanie sztuki budowania wozów, a także zastosowanie nowej, twardszej odmiany brązu pozwoliło Indoeuropejczykom opanować w ciągu kolejnych stuleci i tysiącleci olbrzymie obszary Eurazji od Atlantyku po Birmę. Nie bez znaczenia były przy tym kontakty z innymi ludami, ukształtowanie patriarchatu, wojowniczego nastawienia i dążenia do uzyskania przewagi nad sąsiadami, pochwała podbojów i kult bohaterów. Cechy te okazały się bardzo żywotne mimo upływu tysiącleci, i wciąż obecne były także w społeczności Germanów. Więcej na ten temat w osobnym artykule.

Wyodrębnienie się z etnosu Indoeuropejczyków poszczególnych nacji było związane z dyferencjacją języków indoeuropejskich. Wbrew naiwnym wyobrażeniom niektórych, indoeuropejska migracja nie była procesem ciągłym i ukierunkowanym. Poszczególne plemiona przemieszczały się zapewne dość chaotycznie. W końcu jednak, po wielu wiekach, w miejscu jednolitego języka indoeuropejskiego rozwinęło się wiele różnorodnych języków i dialektów. Szczegóły tego procesu zostały zatarte przez czas i są dziś niezmiernie trudne do zrekonstruowania, tym bardziej, że posługiwać się możemy głównie ustaleniami archeologii, a przemiany kultury materialnej nie zawsze muszą odzwierciedlać przemiany językowe.

Na pewno czynnikiem sprzyjającym różnicowaniu Indoeuropejczyków była ekspansja terytorialna. Jak się jednak wydaje, rozwój węzłów na drzewie rodowym języków czyli odrębnych języków macierzystych grup takich jak italska, celtycka czy właśnie germańska, wymagał przynajmniej czasowego zerwania kontinuum przestrzennego. Mówiąc inaczej, przodkowie późniejszych Germanów musieli nie tylko zająć tereny oddalone od kolebki indoeuropejskiej, ale dodatkowo utracić na jakiś czas wszelką łączność z krewniakami. Przybycie na nowe tereny miało więc postać kolonizacji. Imigranci nie osiedlali się na terenach bezludnych, bo przecież już od dawna egzystowały tu różne nieindoeuropejskie społeczności lokalne. Po ich przybyciu na miejce nowo skolonizowany teren był otoczony ludnością tubylczą, a koloniści zdani byli głównie na siebie, nie utrzymując kontaktów ani z krewniakami pozostałymi w poprzednim miejscu pobytu, ani z innymi grupami kolonistów, które stopniowo pojawiały się na kontynencie europejskim.

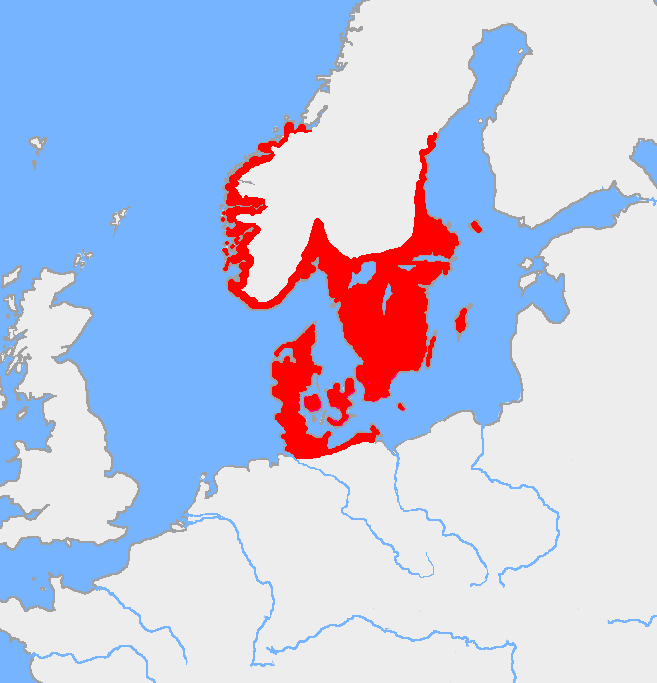

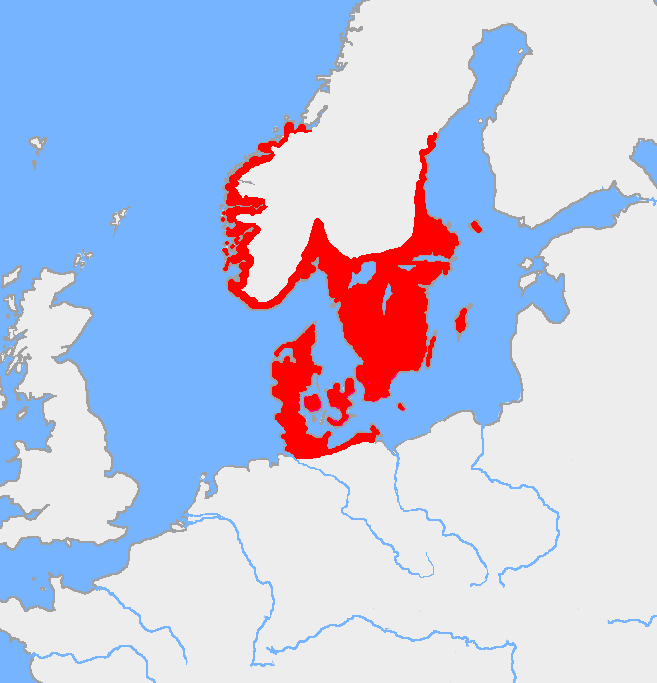

Wyodrębnienie przodków Germanów z głównej masy Indoeuropejczyków zamieszkującej stepy nadczarnomorskie mogło nastąpić około roku 3500 p.n.e. Około roku 2800 p.n.e. Protogermanie mogli już pojawić się w swojej nowej ojczyźnie, obejmującej południową Szwecję, południowe wybrzeża Norwegii, Danię, Szlezwig-Holsztyn, a także przyległe obszary wybrzeża Morza Północnego i Morza Bałtyckiego. Jednak droga ich trwającej kilkaset lat migracji jest przedmiotem spekulacji.

Jedna z rozpatrywanych możliwości to początkowa migracja na północny zachód, na tereny dzisiejszych krajów bałtyckich (Litwa, Łotwa, Estonia) i przebycie Bałtyku łodziami w kierunku zachodnim. Scenariusz taki zdają się popierać nordyckie przekazy, w których Eastmanowie (nordyckie Austmenn, lp Austmaðr) przybywają ze wschodu i podbijają skandynawskich autochtonów.

Drugi scenariusz jest bardziej wiarygodny geograficznie. Jego zwolennicy twierdzą, że Protogermanie wędrowali od stepów czarnomorskich lądem wzdłuż Karpat, tzn. przez południową Polskę i środkowe Niemcy. Dopiero tam skręcili na północ, dotarli do brzegów Bałtyku i Morza Północnego, a część z nich przeprawiła się przez cieśniny duńskie i skolonizowała także południową Szwecję.

Trzeci scenariusz opiera się w większym stopniu na dostępnych danych archeologicznych i przekazuje nam obraz bardziej złożony. Opanowanie Europy środkowej i zachodniej przez Indoeuropejczyków rozpoczyna się od ekspansji kultury majkopskiej w okresie 3500–3000 p.n.e. Dzięki niej Indoeuropejczycy, twórcy kultury jamowej, 3600–2300 p.n.e., zapoznają się z ulepszoną odmianą brązu, która zostaje wykorzystana do produkcji broni (głównie toporów bojowych) zapewniającej przewagę nad innymi ludami. W połączeniu z patriarchalną organizacją społeczną, zamiłowaniem do podbojów i znajomością wozów zaprzężonych w konie lub woły prowadzi to do ekspansji indoeuropejskich wojowników, zdobywających sławę podbojami sąsiadów. Dodatkowym czynnikiem skłaniającym do migracji było występowanie w centralnej Europie kultur neolitycznych, to znaczy takich, które same sobie produkowały żywność. Dla indoeuropejskich harcowników stanowiła ona z pewnością cenny łup.

Rolnictwo i hodowla zwierząt znane były ówczesnym Europejczykom już od setek lat. Na północ od Dunaju, w tym na terenie południowej Polski, rozwijała się kultura ceramiki wstęgowe rytej, 5500–4500 p.n.e. i jej następczyni, kultura lendzielska, V–IV tys. p.n.e. Ich twórcami byli przedindoeuropejscy autochtoni, o których języku można dziś jedynie spekulować. Około roku 4300 p.n.e. na terenie Kujaw z nałożenia przybyłych z południa nowych, neolitycznych sposobów gospodarki na lokalne tradycje mezolityczne myśliwych, rybaków i zbieraczy używających już ceramiki powstała nowa kultura pucharów lejkowatych (4300–2800 p.n.e., według niektórych danych do 1900 p.n.e., często oznaczanej symbolem KPL lub TRB z niemieckiego Trichterrandbecherkultur albo wreszcie TBK z Trichterbecherkultur). Nieco póżniej objęła ona tereny między dolną Łabą a środkową Wisłą, w końcu dotarła także do dzisiejszej Holandii, na tereny południowej Skandynawii (na teren Danii, do okolic Oslo i do płd. Szwecji, gdzie wcześniej rozwijała się mezolityczna ceramiczna kultura Ertebølle-Ellerbek) oraz do części Wołynia i Podola.

Ludność kultury pucharów lejkowatych łączyła stare i nowe tradycje, i zajmowała się tak hodowlą, jak i łowiectwem i rybołóstwem. Uprawiano też zboże, a ziemię pod uprawę spulchniano radłem ciągniętym przez woły. Twórcy KPL zasłynęli także jako budowniczy grobowców megalitycznych. Wydobywali także ozdobny krzemień pasiasty, z którego wykonywali ozdoby.

Od dawna już istnieje wizja zbójeckich wypadów Indoeuropejczyków – „bohaterów” na koniach, którzy wpadają do osady rolników, mordują większość mężczyzn, zmuszają pozostałych przy życiu do niewolnictwa lub co najmniej do oddawania znacznej części żywności, a kobiety wykorzystują między innymi do płodzenia dzieci. Chłopców, którzy rodzą się z tych związków, wychowują na podobnych sobie bohaterów. Indoeuropejscy najeźdźcy nazywają zapewne samych siebie panami, szlachetnymi lub ludźmi wschodu; być może określenie to przetrwało w Skandynawii do czasów historycznych. Mieszkańcy tubylczych osad próbują jakoś znaleźć się w nowej sytuacji, przekupują najeźdźców, by zostawili ich w spokoju, ale też przejmują ich język, zwyczaje i elementy kultury materialnej – zamiast walczyć z najeźdźcami, przyłączają się do nich. Dawny, nieindoeuropejski język tubylców wychodzi przez to z użycia, ale też mowa najeźdźców ulega modyfikacji, zniekształcana w ustach nieprzyzwyczajonych do niej matek, którzy przenoszą na nią nawyki artykulacyjne ze swojego starego języka. Taką wypaczoną mowę przejmują także dzieci. W efekcie indoeuropejska mowa podlega zmianom fonetycznym i gramatycznym, które stopniowo oddalają ją od języka przodków. Kultura tubylców i najeźdźców zespaja się ze sobą. Podtrzymywanie czystych, nienaruszonych tradycji indoeuropejskich byłoby trudne na nowym terenie, choćby dlatego, że lesiste tereny Środkowej Europy wymuszały na Indoeuropejczykach inny niż dotąd rodzaj gospodarki i rezygnację z koczowniczego trybu życia, co faktycznie oznaczało przyjęcie sposobu życia autochtonów.

Nakreślona wizja „podboju”, choć dziś krytykowana przez niektórych (chyba głównie „dla zasady”), pozostaje w rzeczywistości w idealnej zgodności zarówno z danymi lingwistycznymi, jak też i genetycznymi. Jak zaznaczyliśmy na wstępie, te ostatnie nie pomagają nam specjalnie w śledzeniu dróg migracji języków indoeuropejskich, użyteczne są natomiast w śledzeniu migracji mas ludzkich. Dowodzą one niezbicie, że spora część współczesnych mieszkańców Europy to biologiczni potomkowie ludności przedindoeuropejskiej (charakteryzującej się głównie haplotypem R1b), która uległa indoeuropeizacji z przymusu lub z wyboru. Z kolei (kilkunastoprocentowa w krajach germanojęzycznych) domieszka „genów indoeuropejskich” (w szczególności rozpatruje się tu haplotyp R1a1) dowodzi słuszności scenariusza podboju i zniewalania tubylczych kobiet.

Omawiany scenariusz nie zakłada więc wyprawy całego plemienia wozami przez rozległe bory środkowej Europy czy łodziami przez morskie odmęty w poszukiwaniu nowej ojczyzny, ale raczej prowadzone we wszystkich możliwych kierunkach zbójeckie napady. Początkowo dominował kierunek na zachód, bo tam właśnie znajdowały się osady oferujące indoeuropejskim „bohaterom” możliwość zdobycia sławy. Gdy większość tubylców na terenach rozciągających się od Łaby po Wołyń i Podole została już zhołdowana i „nawrócona”, rozwinęły się kultury hybrydowe, łączące dawne nieindoeuropejskie tradycje z nowymi ideami, przybyłymi znad Morza Czarnego. Były to kultura amfor kulistych (3400–2800 p.n.e., KAK) i kultura badeńska (ceramiki promienistej, 3600–2800 p.n.e.). Rozwój zwłaszcza kultury amfor kulistych powstrzymał dalszą ekspansję z terenów stepowych, ale też ona sama zaczęła stopniowo zwiększać swój zasięg, a do tego zaczęła się przekształcać na niektórych terenach, wydając z siebie kulturę ceramiki sznurowej (3200–1800 p.n.e.) i w pewnym przynajmniej sensie kulturę pucharów dzwonowatych (2800–1900 p.n.e.). W zasięgu ich ekspansji znalazły się olbrzymie obszary Europy, po krańce dzisiejszej Portugalii.

(klikając, można obejrzeć obrazek w formacie png)

Europa Środkowa na początku III tysiąclecia p.n.e.

Widoczny jest pierwotny obszar rozwoju kultury jamowej (Yamna, ciemnożółty) oraz tereny jej ekspansji (jasnożółty),

obszary zajęte przez kultury amfor kulistych (Globular Amphora) i ceramiki promienistej (Baden),

wreszcie obszar ekspansji kultury ceramiki sznurowej (Corded Ware).

Źródło: Wikipedia.

Wytwórcy kultury amfor kulistych i ich następcy z okresu kultur ceramiki sznurowej utrzymywali, jak się wydaje, żywe kontakty między osadami. Zaowocowało to względną jednolitością i stałością ich języka. Łączyła ich ta sama kultura materialna i podobne wyobrażenia należące do sfery duchowej (np. swoje naczynia zdobili swastykami, symbolizującymi słońce). Po okresie tym pozostały liczne używane do dziś nazwy geograficzne, w tym nazwy rzek, określane jako hydronimia staroeuropejska. Początkowo Indoeuropejczycy zapewne nie zamieszkiwali zwartych obszarów, pomiędzy zajmowanymi przez nich terenami pozostawały liczne wyspy ludności tubylczej, która wciąż zachowywała przynajmniej swój język. Dopiero na początku II tysiąclecia p.n.e. doszło do ostatecznego rozbicia jedności indoeuropejskiej, wchłonięcia całych ludów tubylczych i w ślad za tym do postępującej dyferencjacji językowej. Poszczególne grupy Indoeuropejczyków stanęły w opozycji do siebie. W wyniku tych procesów oderwały się od siebie takie ludy, jak Celtowie, Italowie, Germanie, Ilirowie, Hellenowie, a także zapewne inne, dziś zapomniane, które później uległy swoim sąsiadom i zasymilowały się z nimi.

Tworzona przez zindoeuropeizowaną ludność kultura amfor kulistych zastąpiła przedindoeuropejską kulturę pucharów lejkowatych głównie na jej centralnym obszarze, tj. m.in. na terenach Polski. Wnioskujemy stąd, że indoeuropejska migracja uległa przyhamowaniu, jeśli nie zastopowaniu, i Protogermanie musieli czekać jeszcze setki lat na dotarcie do swojej nowej ojczyzny.

Tymczasem na obszarach mających stać się nową ojczyzną Pragermanów (Dania, płn. Niemcy, płd. Szwecja) żyły ludy nieindoeuropejskie, które zajmowały się rolnictwem. Jak wspomniano wyżej, neolityczne tradycje dotarły tam wraz z twórcami kultury pucharów lejkowatych. Do Skandynawii rolnictwo i hodowla zwierząt dotarły już w samym końcu V tysiąclecia p.n.e. (około 4000 p.n.e.). Wraz z nimi dotarły monumentalne pochówki megalityczne, dekorowana ceramika i polerowane groty krzemienne. Mieszkańcy środkowej i północnej Skandynawii pozostawali jednak przy mezolitycznym trybie życia co najmniej przez kolejne 3000 lat. Co więcej, na pewnych obszarach południowej Szwecji zrezygnowano wkrótce z rolnictwa i powrócono do myśliwsko-rybacko-zbierackiego sposobu gospodarowania. Ci zbieracze byli twórcami kultury ceramiki dołkowej (Pitted Ware Culture).

In a century or two, all of Denmark and the southern third of Sweden became neolithised and much of the area became dotted with megalithic tombs. The people of the country’s northern two thirds retained an essentially Mesolithic lifestyle into the 1st Millennium BC. Coastal south-eastern Sweden, likewise, reverted from neolithisation to a hunting and fishing economy after only a few centuries, with the Pitted Ware Culture.

The younger TRB in these areas was superseded by the Single Grave culture (EGK) at about 2800 BC. The north-central European megaliths were built primarily during the TRB era.

In c. 2800 BC the Funnel Beaker Culture gave way to the Battle Axe Culture, a regional version of the middle-European Corded Ware phenomenon. Again, diffusion of knowledge or mass migration is disputed. The Battle Axe and Pitted Ware people then coexisted as distinct archaeological entities until c. 2400 BC, when they merged into a fairly homogeneous Late Neolithic culture. This culture produced the finest flintwork in Scandinavian prehistory and the last megalithic tombs.

Budowle megalityczne (megality) występują na obszarze całego świata, w tym również w Europie i Polsce. Początki megalityzmu na terenach Europy sięgają V tysiąclecia p.n.e. Stopniowy zanik idei obserwuje się około 2 tysiąclecia p.n.e. Czasem jednak budowle megalityczne funkcjonowały jeszcze w epoce brązu. Stonehenge straciło swe znaczenie kultowe około 1400 r. p.n.e. Szczególnym typem budowli megalitycznej były megaksylony (gr., mega = wielki; ksylon = drzewo), zbudowane według podobnej idei, ale z innego materiału – z drewna i ziemi.

Spis treści

1 Menhiry, dolmeny i kromlechy

1.1 Dolmeny

1.2 Menhiry

1.3 Kromlechy

2 Grobowce

2.1 Grobowce korytarzowe

2.2 Grobowce galeriowe

2.3 Grobowce skrzynkowe

2.4 Grobowce kamienno-ziemne

3 Kompleksy megalityczne

4 Megality w Polsce

4.1 Kultura pucharów lejkowatych

4.2 Kultura amfor kulistych

5 Megaksylony

6 Zobacz też

7 Bibliografia

8 Linki zewnętrzne

Menhiry, dolmeny i kromlechy

Najprostszymi postaciami budowli megalitycznej były dolmeny, menhiry i kromlechy.

Dolmeny

Dolmen to prostokątny grobowiec, składający się z trzech lub czterech płyt ustawionych pod kątem prostym do podłoża i przykrytych od góry jednym masywnym blokiem. Długość boku dolmeny rzadko przekracza 3 metry, zdarzają się jednak dolmeny większe, wręcz monumentalne. Przykładem może być dolmen z Bagneux we Francji, o wymiarach 16X5 m i wysokości 2,4 m.

Menhiry

Menhirami nazywamy pionowo wkopane w ziemię słupy kamienne. Jeden z największych znajduje się w Bretanii (miejscowość Lockmariaquer) – obecnie rozbity i obalony, miał kiedyś 21-23 m wysokości, prawie 5 m grubości i ważył 350 ton. Menhirami zwieńczano czasem szczyty kurhanów. W okolicy miasta Carnac we Francji znajduje się „aleja” wyznaczona menhirami.

Kromlechy

Z innych stanowisk europejskich znane są też konstrukcje koliste – zwane kromlechami. Na Wyspach Brytyjskich naliczono ich około tysiąca. Mają średnicę od kilku do kilkudziesięciu metrów – do tego rodzaju zaliczane jest gigantyczne Stonehenge.

Grobowce

Bardziej złożonymi strukturami megalitycznymi są grobowce korytarzowe, galeriowe i skrzynkowe oraz grobowce o konstrukcji kamienno-ziemnej.

Grobowce korytarzowe

Grobowce korytarzowe charakteryzują się komorą grobową zbudowaną z potężnych płyt kamiennych. Prowadzi do nich również kamienny, długi korytarz. Grobowiec taki przysypywano nasypem kurhanu. Najbardziej rozwiniętą formą grobowca korytarzowego był tolos. Komora tolosa osiągała olbrzymie rozmiary. Do najbardziej znanych należy tolos z Newgrange w Irlandii.

Grobowce galeriowe

Grobowce galeriowe nie mają korytarza. Są to wąskie i długie komory. Ich długość wielokrotnie przekracza szerokość. Najdłuższe osiągają 60 m długości, przy zaledwie 5 metrach szerokości (np. grobowiec w West Kennet, Anglia). Odmianą grobowców galeriowych są grobowce transeptowe – komora grobowca transeptowego była zaopatrzona w symetryczne nawy.

Grobowce skrzynkowe

Grobowce skrzynkowe to z reguły niewielkie budowle, osiągające kilka metrów długości, zbudowane z cienkich płyt, bez korytarza, za to przykryte kurhanem.

Grobowce kamienno-ziemne

Głównym elementem budowlanym tych grobowców są specjalnie ukształtowane masy ziemne. Przykłady takich grobowców spotykane są w Wielkiej Brytanii, Francji, Niemczech, Danii i Polsce (tzw. grobowce kujawskie). Są to struktury bezkomorowe, różniące się od typowych megalitów zarówno strukturą jak i pochodzeniem. Być może na ich kształt wywarły wpływ wczesnorolnicze kultury naddunajskie.

Kompleksy megalityczne

Niektóre z wymienionych wyżej budowli megalitycznych wchodziły w skład dużych kompleksów, których przeznaczenie nie zostało jeszcze wyjaśnione. Prawdopodobnie miały one charakter kultowy, niektórzy naukowcy sugerują też ich związek z obserwacjami astronomicznymi. Do najbardziej znanych należy kompleks na Salisbury Plain w Anglii – tam właśnie znajduje się Stonehenge i inne kromlechy, np. w Avebury. Do kompleksów megalitycznych należy też zaliczyć wspomniany rozległy kompleks w okolicach Carnac, w Bretanii, utworzony przez tysiące menhirów i liczne wielkie grobowce.

Megality w Polsce

Budowle megalityczne na obszarach Polski związane są z występowaniem dwóch kultur: kultury pucharów lejkowatych i późniejszej kultury amfor kulistych.

Kultura pucharów lejkowatych

Kultura ta w III tysiącleciu p.n.e. była rozprzestrzeniona na rozległych połaciach Europy środkowej i północnej. Jej pozostałościami są m.in. rozmaite grobowce megalityczne. Z terenów Polski znane są z tego okresu długie, bezkomorowe kopce ziemne, zwane kopcami kujawskimi. Miały one kształt wydłużonego trapezu zbliżonego do trójkąta, szerokość podstawy od 6-15 metrów, długość od 40 do 150 metrów, a pierwotna wysokość szacowana jest na ok. 3 m. Obstawa grobowca zrobiona była z dużych głazów. W najszerszej części budowli, zwanej podstawą lub czołem grobowca, znajdował się pojedynczy zazwyczaj grób, czasem jednak również więcej pochówków. Między grobem a kamieniami podstawy znajdowało się niekiedy sanktuarium (świątynia grobowa). Grobowce kujawskie wznoszono w okresie od IV–III tysiąclecia p.n.e. Najbardziej znane znajdują się obecnie w Sarnowie i Wietrzychowicach na Kujawach, a także w okolicy Łupawy na Pomorzu. Podobne struktury znajdują się także na Pomorzu Zachodnim w okolicach Dolic (Krępcewo, Pomiętowo), Koszalina oraz Przelewic (Krzynki).

Kultura amfor kulistych

W drugiej połowie III tysiąclecia p.n.e. na terenach Polski zaczęły się pojawiać zupełnie inne grobowce megalityczne, charakterystyczne dla kultury amfor kulistych. Były to grobowce skrzyniowe, wykonane z dużych płyt i przykryte wielkim głazem lub głazami. Ich długość wynosiła od 2,5-6 metrów, a szerokość ok. 1-2 metrów. Skrzynie te wkopywane były pod powierzchnię ziemi. Znaleziono w nich zbiorowe pochówki, czasem też ofiary ze zwierząt.

Megaksylony

Grobowiec megaksylonowy nawiązywał formą do grobowców megalitycznych typu kujawskiego, jednakże filarem jego konstrukcji były duże pnie. Na ziemiach polskich znaleziono takie grobowce w Słonowicach, na południu kraju. Nietrudno wyjaśnić, czemu budowniczowie megaksylonów odeszli od stosowania kamienia na rzecz drewna – na Kujawach i Pomorzu nie brak polodowcowych głazów narzutowych. Na południu są one rzadkością. Przywiązanie do idei budowli megalitycznej wymusiło zatem zastosowanie innego materiału. Ściany megaksylonów słonowickich zrobione były z potężnej palisady wkopanych pni o średnicy ok. 30 cm każdy. Szerokość grobu wynosiła około 5 m, a głębokość (powyżej poziomu ziemi) ok. 3 m. Megaksylon pochylał się ku zachodowi. Oczywiście do dnia dzisiejszego zachowały się tylko rowki fundamentowe, w których ustawiano pnie grobowca, z dobrze widocznymi, znacznie ciemniejszymi kołami – pozostałością po rozłożonych pionowych belkach. Po rozłożeniu drewna nasypy zostały rozmyte przez deszcze. Zachowały się jednak pochówki. Do dziś odkryto w Słonowicach sześć megaksylonów, usytuowanych równolegle, posiadających wspólne cechy, ale nie identycznych i różniących się rozmiarami. Tylko dwóm z nich towarzyszą rowy, z których wybierano ziemię do zasypania grobów. Być może zatem pozostałe są puste. Pochówki nie zawierają żadnego ciekawego wyposażenia, ciała zostały zasypane kamieniami i ziemią. Czasem badacze znajdują jakieś naczynie lub wyroby miedziane. Badania w Słonowicach rozpoczęto w 1979 roku, są obecnie w toku, a ich końca na razie nie widać. Więcej na ten temat można przeczytać na stronie internetowej Słonowice nad rzeką Małoszówką, poświęconej wykopaliskom.

Stonehenge

Skocz do: nawigacji, wyszukiwania

Stonehenge, Avebury i pobliskie miejsca kultowea

Obiekt z listy światowego dziedzictwa UNESCO

Stonehenge.jpg

Kraj Wielka Brytania

Typ kultura

Spełniane kryterium I, II, III

Charakterystyka #373

Regionb Europa i Ameryka Północna

Historia wpisania na listę

Wpisanie na listę 1986

na 10. sesji

Dokonane zmiany 2008

a Oficjalna nazwa wpisana na liście UNESCO

b Oficjalny podział dokonany przez UNESCO

Galeria zdjęć w Wikimedia Commons Galeria zdjęć w Wikimedia Commons

Wschód słońca nad Stonehenge w dniu przesilenia letniego

Zachód słońca nad Stonehenge

Stonehenge – jedna z najsłynniejszych europejskich budowli megalitycznych, pochodząca z epoki neolitu oraz brązu. Megalit położony jest w odległości 13 km od miasta Salisbury w hrabstwie Wiltshire w południowej Anglii. Najprawdopodobniej związany był z kultem księżyca i słońca. Księżyc mógł symbolizować tutaj kobietę (biorąc pod uwagę jej comiesięczną menstruację), słońce – mężczyznę. Składa się z wałów ziemnych otaczających duży zespół stojących kamieni. Obiekt od 1986 jest wpisany na listę światowego dziedzictwa UNESCO wraz z Avebury oraz innymi okolicznymi stanowiskami neolitycznnymi. Obiekt znajduje się pod nadzorem angielskiego Scheduled Ancient Monument. Obiektem zarządza organizacja English Heritage.

Spis treści

1 Etymologia

2 Historia

3 Budowa

4 Archeoastronomia

5 Replika

6 Zobacz też

7 Bibliografia

8 Linki zewnętrzne

Etymologia

Nazwa pochodzi z języka staroangielskiego, od słów stān – kamień (ang. stone) i hencg – otaczać (ang. hinge) lub hen(c)en (szubienica). Ze słowa henge powstało słowo henges – kręgi – którym teraz są nazywane tego typu obiekty.

Historia

W rozwoju budowli wyróżnia się następujące okresy chronologiczne:

Stonehenge 1: około 2950–2900 p.n.e.

Stonehenge 2: około 2900–2400 p.n.e.

Stonehenge 3a: od około 2600 p.n.e.

Stonehenge 3b: 2440–2100 p.n.e.

Stonehenge 3c:

Stonehenge 3d: 2270–1930 p.n.e.

Stonehenge 3e:

Stonehenge 3f: do około 1600 p.n.e.

Miejsce, w którym powstała budowla Stonehenge, zyskało znaczenie kulturowe przed rokiem 2950 p.n.e. Świadczą o tym znajdujące się na zewnątrz megalitu groby datowane nawet na ok. 3100 rok p.n.e. oraz usypany z ziemi pierścień datowany również na ten okres.

Budowa

Stonehenge faza pierwsza

Plan Stonehenge

Stonehenge składa się z kolejnych elementów, ustawianych w dużych odstępach czasowych (sanktuarium powstawało stopniowo, przez ponad tysiąc lat). Aleja wiodąca do Stonehenge ciągnie się na długości około 3 km i jest szeroka na 11 m. Pierwotnie jej krawędzie ograniczał wał ziemny. Podobna konstrukcja okala całe stanowisko. Pierwszym elementem na drodze z alei do wnętrza kręgów jest Heel Stone, ustawiony około 2600 roku p.n.e. Mniej więcej w tym samym czasie, wewnątrz kredowych wałów pojawiają się również 4 Station Stones. Zewnętrznym, pierwszym kamiennym kręgiem, jest pierścień 30 kamieni (zwanych Sarsenami) o średnicy 40 m, datowany na ok. 2450 rok p.n.e. Wewnątrz niego znajduje się pierścień egzotycznie wyglądających, błękitnych kamieni (Bluestones). Do samego wnętrza Stonehenge prowadzi jeszcze monumentalna podkowa złożona z pięciu trylitów (o wysokości około 9m), oraz mała podkowa złożona z 30 Bluestones. Obydwie podkowy otwarte są w kierunku alei. W samym centrum Stonehenge znajduje się tzw. Altar Stone – dziś przewrócony.

Ponadto, wewnątrz kredowych wałów, archeologiczne badania wykazały istnienie tzw. Aubrey Holes, czyli 56 jam o średnicy 2 m i głębokości około metra. G. Hawkins, w swoim artykule „A Neolithic Computer” (dla Nature, 27 stycznia 1964), postawił tezę mówiącą, jakoby Aubrey Holes były używane jako specyficzny komputer do przewidywania zaćmień słońca i księżyca, lecz teoria ta w krótkim czasie została obalona. Jamy prawdopodobnie są śladem po dodatkowej, drewnianej konstrukcji otaczającej kamienne kręgi.

Na obszarze stanowiska – na zewnątrz pierścienia Sarsenów – znaleziono również dwa pierścienie mniejszych jam, nazwanych kolejno X i Y, w liczbie 30 i 29. Zwraca uwagę to, że liczba otworów odpowiada średniej ilości dni w miesiącu synodycznym.

Oś podkowy wyznacza kierunek, z którego wschodzi słońce w najdłuższym dniu w roku, podczas letniego przesilenia. Sanktuarium wzniesione jest z dwóch rodzajów kamienia. Największe, granitowe bloki pochodzą z okolic Marlborough Downs (około 30 km na północ od Stonehenge), natomiast mniejsze, błękitne skały – z Pembrokeshire w Walii, położonego około 250 km od budowli.

Archeoastronomia

Stonehenge jest ukierunkowane północnowschodnio-południowozachodnio (NE-SW). Wielka debata na temat znaczenia Stonehenge wytworzyła się po publikacji w 1963 roku Stonehenge Decoded przez angielskiego astronoma Geralda Hawkinsa, który twierdził, że odnalazł wiele powiązań między ustawieniem głazów a pozycją obiektów niebieskich i słońca. Uważał, iż Stonehenge mogło być używane do przewidywania zaćmień. Jego badania zostały szeroko uznane w środowisku naukowym, jako że do ich przeprowadzania używał obliczeń komputerowych (wtedy należących do rzadkości). Następcami w badaniach byli C. A. Newham wraz z Sir Fredem Hoylem oraz inżynier Alexander Thom, który poświęcił na badania nad Stonehenge 20 lat. Ich teorie były ostro krytykowane przez Richarda Atkinsona i innych.

Stonehenge

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

Jump to: navigation, search

For other uses, see Stonehenge (disambiguation).

Page semi-protected

UNESCO World Heritage Site Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites

Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List

Stonehenge in 2007

Country United Kingdom

Type Cultural

Criteria i, ii, iii

Reference 373

UNESCO region Europe and North America

Inscription history

Inscription 1986 (10th Session)

Stonehenge is located in Wiltshire

Map of Wiltshire showing the location of Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England, about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Amesbury and 8 miles (13 km) north of Salisbury. One of the most famous sites in the world, Stonehenge is the remains of a ring of standing stones set within earthworks. It is in the middle of the most dense complex of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments in England, including several hundred burial mounds.[1]

Archaeologists believe it was built anywhere from 3000 BC to 2000 BC. Radiocarbon dating in 2008 suggested that the first stones were raised between 2400 and 2200 BC,[2] whilst another theory suggests that bluestones may have been raised at the site as early as 3000 BC.[3][4][5]

The surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. The site and its surroundings were added to the UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites in 1986 in a co-listing with Avebury Henge. It is a national legally protected Scheduled Ancient Monument. Stonehenge is owned by the Crown and managed by English Heritage, while the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust.[6][7]

Archaeological evidence found by the Stonehenge Riverside Project in 2008 indicates that Stonehenge could have been a burial ground from its earliest beginnings.[8] The dating of cremated remains found on the site indicate that deposits contain human bone from as early as 3000 BC, when the ditch and bank were first dug. Such deposits continued at Stonehenge for at least another 500 years.[9] The site is a place of religious significance and pilgrimage in Neo-Druidry.

1 Etymology

2 Early history

2.1 Before the monument (8000 BC forward)

2.2 Stonehenge 1 (ca. 3100 BC)

2.3 Stonehenge 2 (ca. 3000 BC)

2.4 Stonehenge 3 I (ca. 2600 BC)

2.5 Stonehenge 3 II (2600 BC to 2400 BC)

2.6 Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

2.7 Stonehenge 3 V (1930 BC to 1600 BC)

2.8 After the monument (1600 BC on)

3 Function and construction

4 Modern history

4.1 Folklore

4.1.1 “Heel Stone”, “Friar’s Heel” or “Sun-stone”

4.1.2 Arthurian legend

4.2 16th century to present

4.2.1 Neopaganism

4.2.2 Setting and access

4.3 Archaeological research and restoration

5 Gallery

6 See also 7 References

8 Bibliography

9 External links

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary cites Ælfric’s 10th-century glossary, in which henge-cliff is given the meaning “precipice”, or stone, thus the stanenges or Stanheng “not far from Salisbury” recorded by 11th-century writers are “supported stones”. William Stukeley in 1740 notes, “Pendulous rocks are now called henges in Yorkshire… I doubt not, Stonehenge in Saxon signifies the hanging stones”.[10] Christopher Chippindale’s Stonehenge Complete gives the derivation of the name Stonehenge as coming from the Old English words stān meaning “stone”, and either hencg meaning “hinge” (because the stone lintels hinge on the upright stones) or hen(c)en meaning “hang” or “gallows” or “instrument of torture”. Like Stonehenge’s trilithons, medieval gallows consisted of two uprights with a lintel joining them, rather than the inverted L-shape more familiar today.

The “henge” portion has given its name to a class of monuments known as henges.[10] Archaeologists define henges as earthworks consisting of a circular banked enclosure with an internal ditch.[11] As often happens in archaeological terminology, this is a holdover from antiquarian usage, and Stonehenge is not truly a henge site as its bank is inside its ditch. Despite being contemporary with true Neolithic henges and stone circles, Stonehenge is in many ways atypical – for example, at over 7.3 metres (24 ft) tall, its extant trilithons supporting lintels held in place with mortise and tenon joints, make it unique.[12][13]

Early history

Plan of Stonehenge in 2004. After Cleal et al. and Pitts. Italicised numbers in the text refer to the labels on this plan. Trilithon lintels omitted for clarity. Holes that no longer, or never, contained stones are shown as open circles. Stones visible today are shown coloured

Mike Parker Pearson, leader of the Stonehenge Riverside Project based at Durrington Walls, noted that Stonehenge appears to have been associated with burial from the earliest period of its existence:

Stonehenge was a place of burial from its beginning to its zenith in the mid third millennium BC The cremation burial dating to Stonehenge’s sarsen stones phase is likely just one of many from this later period of the monument’s use and demonstrates that it was still very much a domain of the dead.[9]

— Mike Parker Pearson

Stonehenge evolved in several construction phases spanning at least 1,500 years. There is evidence of large-scale construction on and around the monument that perhaps extends the landscape’s time frame to 6,500 years. Dating and understanding the various phases of activity is complicated by disturbance of the natural chalk by periglacial effects and animal burrowing, poor quality early excavation records, and a lack of accurate, scientifically verified dates. The modern phasing most generally agreed to by archaeologists is detailed below. Features mentioned in the text are numbered and shown on the plan, right.

Before the monument (8000 BC forward)

Archaeologists have found four, or possibly five, large Mesolithic postholes (one may have been a natural tree throw), which date to around 8000 BC, beneath the nearby modern tourist car-park. These held pine posts around 0.75 metres (2 ft 6 in) in diameter which were erected and eventually rotted in situ. Three of the posts (and possibly four) were in an east-west alignment which may have had ritual significance; no parallels are known from Britain at the time but similar sites have been found in Scandinavia. Salisbury Plain was then still wooded but 4,000 years later, during the earlier Neolithic, people built a causewayed enclosure at Robin Hood’s Ball and long barrow tombs in the surrounding landscape. In approximately 3500 BC, a Stonehenge Cursus was built 700 metres (2,300 ft) north of the site as the first farmers began to clear the trees and develop the area.

Stonehenge 1 (ca. 3100 BC)

Stonehenge 1. After Cleal et al.

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch enclosure made of Late Cretaceous (Santonian Age) Seaford Chalk, (7 and 8), measuring about 110 metres (360 ft) in diameter, with a large entrance to the north east and a smaller one to the south (14). It stood in open grassland on a slightly sloping spot.[14] The builders placed the bones of deer and oxen in the bottom of the ditch, as well as some worked flint tools. The bones were considerably older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch, and the people who buried them had looked after them for some time prior to burial. The ditch was continuous but had been dug in sections, like the ditches of the earlier causewayed enclosures in the area. The chalk dug from the ditch was piled up to form the bank. This first stage is dated to around 3100 BC, after which the ditch began to silt up naturally. Within the outer edge of the enclosed area is a circle of 56 pits (13), each about a metre (3 ft 3 in) in diameter, known as the Aubrey holes after John Aubrey, the 17th-century antiquarian who was thought to have first identified them. The pits may have contained standing timbers creating a timber circle, although there is no excavated evidence of them. A recent excavation has suggested that the Aubrey Holes may have originally been used to erect a bluestone circle.[15] If this were the case, it would advance the earliest known stone structure at the monument by some 500 years. A small outer bank beyond the ditch could also date to this period.

In 2013 a team of archaeologists, led by Professor Mike Parker Pearson, excavated more than 50,000 cremated bones of 63 individuals buried at Stonehenge.[3][4] These remains had originally been buried individually in the Aubrey holes, exhumed during a previous excavation conducted by William Hawley in 1920, been considered unimportant by him, and subsequently re-interred together in one hole, Aubrey Hole 7, in 1935.[16] Physical and chemical analysis of the remains has shown that the cremated were almost equally men and women, and included some children.[3][4] As there was evidence of the underlying chalk beneath the graves being crushed by substantial weight, the team concluded that the first bluestones brought from Wales were probably used as grave markers.[3][4] Radiocarbon dating of the remains has put the date of the site 500 years earlier than previously estimated, to around 3,000 BCE.[3][4]

Analysis of animal teeth found at nearby Durrington Walls, thought to be the “builders camp”, suggests that as many as 4,000 people gathered at the site for the mid-winter and mid-summer festivals; the evidence showed that the animals had been slaughtered around 9 months or 15 months after their spring birth. Strontium isotope analysis of the animal teeth showed that some had travelled from as far afield as the Scottish Highlands for the celebrations.[4][5]

Stonehenge 2 (ca. 3000 BC)

Evidence of the second phase is no longer visible. The number of postholes dating to the early 3rd millennium BC suggest that some form of timber structure was built within the enclosure during this period. Further standing timbers were placed at the northeast entrance, and a parallel alignment of posts ran inwards from the southern entrance. The postholes are smaller than the Aubrey Holes, being only around 0.4 metres (16 in) in diameter, and are much less regularly spaced. The bank was purposely reduced in height and the ditch continued to silt up. At least twenty-five of the Aubrey Holes are known to have contained later, intrusive, cremation burials dating to the two centuries after the monument’s inception. It seems that whatever the holes’ initial function, it changed to become a funerary one during Phase 2. Thirty further cremations were placed in the enclosure’s ditch and at other points within the monument, mostly in the eastern half. Stonehenge is therefore interpreted as functioning as an enclosed cremation cemetery at this time, the earliest known cremation cemetery in the British Isles. Fragments of unburnt human bone have also been found in the ditch-fill. Dating evidence is provided by the late Neolithic grooved ware pottery that has been found in connection with the features from this phase.

Stonehenge 3 I (ca. 2600 BC)

Graffiti on the sarsen stones. Below are ancient carvings of a dagger and an axe

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming ‘crescents’); however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. The bluestones (some of which are made of dolerite, an igneous rock), were thought for much of the 20th century to have been transported by humans from the Preseli Hills, 150 miles (240 km) away in modern-day Pembrokeshire in Wales. Another theory that has recently gained support is that they were brought much nearer to the site as glacial erratics by the Irish Sea Glacier.[17] Other standing stones may well have been small sarsens (limestones), used later as lintels. The stones, which weighed about four tons, consisted mostly of spotted Ordovician dolerite but included examples of rhyolite, tuff and volcanic and calcareous ash; in total around 20 different rock types are represented. Each monolith measures around 2 metres (6.6 ft) in height, between 1 m and 1.5 m (3.3–4.9 ft) wide and around 0.8 metres (2.6 ft) thick. What was to become known as the Altar Stone (1), is almost certainly derived from either Carmarthenshire or the Brecon Beacons and may have stood as a single large monolith.

The north-eastern entrance was widened at this time, with the result that it precisely matched the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of the period. This phase of the monument was abandoned unfinished, however; the small standing stones were apparently removed and the Q and R holes purposefully backfilled. Even so, the monument appears to have eclipsed the site at Avebury in importance towards the end of this phase.

The Heelstone (5), a Tertiary sandstone, may also have been erected outside the north-eastern entrance during this period. It cannot be accurately dated and may have been installed at any time during phase 3. At first it was accompanied by a second stone, which is no longer visible. Two, or possibly three, large portal stones were set up just inside the north-eastern entrance, of which only one, the fallen Slaughter Stone (4), 4.9 metres (16 ft) long, now remains. Other features, loosely dated to phase 3, include the four Station Stones (6), two of which stood atop mounds (2 and 3). The mounds are known as “barrows” although they do not contain burials. Stonehenge Avenue, (10), a parallel pair of ditches and banks leading 2 miles (3.2 km) to the River Avon, was also added. Two ditches similar to Heelstone Ditch circling the Heelstone (which was by then reduced to a single monolith) were later dug around the Station Stones.

Stonehenge 3 II (2600 BC to 2400 BC)

Plan of the central stone structure today; After Johnson 2008

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous Oligocene-Miocene sarsen stones (shown grey on the plan) were brought to the site. They may have come from a quarry, around 25 miles (40 km) north of Stonehenge on the Marlborough Downs, or they may have been collected from a “litter” of sarsens on the chalk downs, closer to hand. The stones were dressed and fashioned with mortise and tenon joints before 30 were erected as a 33 metres (108 ft) diameter circle of standing stones, with a ring of 30 lintel stones resting on top. The lintels were fitted to one another using another woodworking method, the tongue and groove joint. Each standing stone was around 4.1 metres (13 ft) high, 2.1 metres (6 ft 11 in) wide and weighed around 25 tons. Each had clearly been worked with the final visual effect in mind; the orthostats widen slightly towards the top in order that their perspective remains constant when viewed from the ground, while the lintel stones curve slightly to continue the circular appearance of the earlier monument. The inward-facing surfaces of the stones are smoother and more finely worked than the outer surfaces. The average thickness of the stones is 1.1 metres (3 ft 7 in) and the average distance between them is 1 metre (3 ft 3 in). A total of 75 stones would have been needed to complete the circle (60 stones) and the trilithon horseshoe (15 stones). Unless some of the sarsens have since been removed from the site, the ring appears to have been left incomplete. The lintel stones are each around 3.2 metres (10 ft), 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) wide and 0.8 metres (2 ft 7 in) thick. The tops of the lintels are 4.9 metres (16 ft) above the ground.

Within this circle stood five trilithons of dressed sarsen stone arranged in a horseshoe shape 13.7 metres (45 ft) across with its open end facing north east. These huge stones, ten uprights and five lintels, weigh up to 50 tons each. They were linked using complex jointing. They are arranged symmetrically. The smallest pair of trilithons were around 6 metres (20 ft) tall, the next pair a little higher and the largest, single trilithon in the south west corner would have been 7.3 metres (24 ft) tall. Only one upright from the Great Trilithon still stands, of which 6.7 metres (22 ft) is visible and a further 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) is below ground.

The images of a “dagger” and 14 “axeheads” have been carved on one of the sarsens, known as stone 53; further carvings of axeheads have been seen on the outer faces of stones 3, 4, and 5. The carvings are difficult to date, but are morphologically similar to late Bronze Age weapons; recent laser scanning work on the carvings supports this interpretation. The pair of trilithons in the north east are smallest, measuring around 6 metres (20 ft) in height; the largest, which is in the south west of the horseshoe, is almost 7.5 metres (25 ft) tall.

This ambitious phase has been radiocarbon dated to between 2600 and 2400 BC,[18] slightly earlier than the Stonehenge Archer, discovered in the outer ditch of the monument in 1978, and the two sets of burials, known as the Amesbury Archer and the Boscombe Bowmen, discovered 3 miles (4.8 km) to the west. At about the same time, a large timber circle and a second avenue were constructed 2 miles (3.2 km) away at Durrington Walls overlooking the River Avon. The timber circle was orientated towards the rising sun on the midwinter solstice, opposing the solar alignments at Stonehenge, whilst the avenue was aligned with the setting sun on the summer solstice and led from the river to the timber circle. Evidence of huge fires on the banks of the Avon between the two avenues also suggests that both circles were linked, and they were perhaps used as a procession route on the longest and shortest days of the year. Parker Pearson speculates that the wooden circle at Durrington Walls was the centre of a “land of the living”, whilst the stone circle represented a “land of the dead”, with the Avon serving as a journey between the two.[19]

Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

This phase saw further rearrangement of the bluestones. They were arranged in a circle between the two rings of sarsens and in an oval at the centre of the inner ring. Some archaeologists argue that some of these bluestones were from a second group brought from Wales. All the stones formed well-spaced uprights without any of the linking lintels inferred in Stonehenge 3 III. The Altar Stone may have been moved within the oval at this time and re-erected vertically. Although this would seem the most impressive phase of work, Stonehenge 3 IV was rather shabbily built compared to its immediate predecessors, as the newly re-installed bluestones were not well-founded and began to fall over. However, only minor changes were made after this phase.

Stonehenge 3 V (1930 BC to 1600 BC)

Soon afterwards, the north eastern section of the Phase 3 IV bluestone circle was removed, creating a horseshoe-shaped setting (the Bluestone Horseshoe) which mirrored the shape of the central sarsen Trilithons. This phase is contemporary with the Seahenge site in Norfolk.

After the monument (1600 BC on)

Computer rendering of the overall site

The Y and Z Holes are the last known construction at Stonehenge, built about 1600 BC, and the last usage of it was probably during the Iron Age. Roman coins and medieval artefacts have all been found in or around the monument but it is unknown if the monument was in continuous use throughout British prehistory and beyond, or exactly how it would have been used. Notable is the massive Iron Age hillfort Vespasian’s Camp built alongside the Avenue near the Avon. A decapitated 7th century Saxon man was excavated from Stonehenge in 1923.[20] The site was known to scholars during the Middle Ages and since then it has been studied and adopted by numerous groups.

Function and construction

See also: Archaeoastronomy and Stonehenge

In the Mesolithic period, two large wooden posts were erected at the site. Today, they are marked by circular white marks in the middle of the car park.

Stonehenge was produced by a culture that left no written records. Many aspects of Stonehenge remain subject to debate. This multiplicity of theories, some of them very colourful, are often called the “mystery of Stonehenge”. A number of myths surround the stones.[21]

There is little or no direct evidence for the construction techniques used by the Stonehenge builders. Over the years, various authors have suggested that supernatural or anachronistic methods were used, usually asserting that the stones were impossible to move otherwise. However, conventional techniques, using Neolithic technology as basic as shear legs, have been demonstrably effective at moving and placing stones of a similar size. Proposed functions for the site include usage as an astronomical observatory or as a religious site.

More recently two major new theories have been proposed. Professor Geoffrey Wainwright OBE, FSA, president of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and Professor Timothy Darvill, OBE of Bournemouth University have suggested that Stonehenge was a place of healing – the primeval equivalent of Lourdes.[22] They argue that this accounts for the high number of burials in the area and for the evidence of trauma deformity in some of the graves. However they do concede that the site was probably multifunctional and used for ancestor worship as well.[23] Isotope analysis indicates that some of the buried individuals were from other regions. A teenage boy buried approximately 1550 BC was raised near the Mediterranean Sea; a metal worker from 2300 BC dubbed the “Amesbury Archer” grew up near the alpine foothills of Germany; and the “Boscombe Bowmen” probably arrived from Wales or Brittany, France.[24] On the other hand, Professor Mike Parker Pearson of Sheffield University has suggested that Stonehenge was part of a ritual landscape and was joined to Durrington Walls by their corresponding avenues and the River Avon. He suggests that the area around Durrington Walls Henge was a place of the living, whilst Stonehenge was a domain of the dead. A journey along the Avon to reach Stonehenge was part of a ritual passage from life to death, to celebrate past ancestors and the recently deceased.[19] Both explanations were first mooted in the 12th century by Geoffrey of Monmouth (below), who extolled the curative properties of the stones and was also the first to advance the idea that Stonehenge was constructed as a funerary monument. Whatever religious, mystical or spiritual elements were central to Stonehenge, its design includes a celestial observatory function, which might have allowed prediction of eclipse, solstice, equinox and other celestial events important to a contemporary religion.[25]

Another theory, brought forth in 2012, suggests that the monument was intended to unify the different peoples of the British island. This theory suggests that the massive amount of labour involved in the construction of Stonehenge necessitated inter-regional cooperation,[21] especially as many of the stones were moved over very long distances, for example from quarries in Wales.[26]

Modern history

Folklore

The Heelstone

“Heel Stone”, “Friar’s Heel” or “Sun-stone”

The Heel Stone lies just outside the main entrance to the henge, next to the present A344 road. It is a rough stone, 16 feet (4.9 m) above ground, leaning inwards towards the stone circle. It has been known by many names in the past, including “Friar’s Heel” and “Sun-stone”. Today it is uniformly referred to as the Heel Stone or Heelstone. At summer solstice an observer standing within the stone circle, looking north-east through the entrance, would see the sun rise above the heel stone.

A folk tale, which cannot be dated earlier than the seventeenth century, relates the origin of the Friar’s Heel reference.

The Devil bought the stones from a woman in Ireland, wrapped them up, and brought them to Salisbury plain. One of the stones fell into the Avon, the rest were carried to the plain. The Devil then cried out, “No-one will ever find out how these stones came here!”. A friar replied, “That’s what you think!”, whereupon the Devil threw one of the stones at him and struck him on the heel. The stone stuck in the ground and is still there.

Some claim “Friar’s Heel” is a corruption of “Freyja’s He-ol” from the Germanic goddess Freyja and the Welsh word for track. The Heel Stone lies beside the end portion of Stonehenge Avenue.

A simpler explanation for the name might be that the stone heels, or leans.

The name is not unique; there was a monolith with the same name recorded in the 19th century by antiquarian Charles Warne at Long Bredy in Dorset.[27]

Arthurian legend

A giant helps Merlin build Stonehenge. From a manuscript of the Roman de Brut by Wace in the British Library (Egerton 3028). This is the oldest known depiction of Stonehenge.

In the 12th century, Geoffrey of Monmouth included a fanciful story in his work Historia Regum Britanniae that attributed the monument’s construction to Merlin.[28] Geoffrey’s story spread widely, appearing in more and less elaborate form in adaptations of his work such as Wace’s Norman French Roman de Brut, Layamon’s Middle English Brut, and the Welsh Brut y Brenhinedd.

According to Geoffrey, the rocks of Stonehenge were healing rocks, called the Giant’s dance, which Giants had brought from Africa to Ireland for their healing properties. The fifth-century king Aurelius Ambrosius wished to erect a memorial to 3,000 nobles slain in battle against the Saxons and buried at Salisbury, and at Merlin’s advice chose Stonehenge. The king sent Merlin, Uther Pendragon (Arthur’s father), and 15,000 knights, to remove it from Ireland, where it had been constructed on Mount Killaraus by the Giants. They slew 7,000 Irish but, as the knights tried to move the rocks with ropes and force, they failed. Then Merlin, using “gear” and skill, easily dismantled the stones and sent them over to Britain, where Stonehenge was dedicated. After it had been rebuilt near Amesbury, Geoffrey further narrates how first Ambrosius Aurelianus, then Uther Pendragon, and finally Constantine III, were buried inside the “Giants’ Ring of Stonehenge”. In many places in his Historia Regum Britanniae Geoffrey mixes British legend and his own imagination; it is intriguing that he connects Ambrosius Aurelianus with this prehistoric monument as there is place-name evidence to connect Ambrosius with nearby Amesbury.

In another legend of Saxons and Britons, in 472 the invading king Hengist invited Brythonic warriors to a feast, but treacherously ordered his men to draw their weapons from concealment and fall upon the guests, killing 420 of them. Hengist erected the stone monument—Stonehenge—on the site to show his remorse for the deed.[29]

16th century to present

With farm carts, ca. 1885

Stonehenge has changed ownership several times since King Henry VIII acquired Amesbury Abbey and its surrounding lands. In 1540 Henry gave the estate to the Earl of Hertford. It subsequently passed to Lord Carleton and then the Marquess of Queensbury. The Antrobus family of Cheshire bought the estate in 1824. During World War I an aerodrome was built on the downs just to the west of the circle and, in the dry valley at Stonehenge Bottom, a main road junction was built, along with several cottages and a cafe. The Antrobus family sold the site after their last heir was killed in the fighting in France. The auction by Knight Frank & Rutley estate agents in Salisbury was held on 21 September 1915 and included “Lot 15. Stonehenge with about 30 acres, 2 rods, 37 perches of adjoining downland”. [c. 12.44 ha][30]

Sunrise over Stonehenge on the summer solstice, 21 June 2005

Cecil Chubb bought the site for £6,600 and gave it to the nation three years later. Although it has been speculated that he purchased it at the suggestion of—or even as a present for—his wife, in fact he bought it on a whim, as he believed a local man should be the new owner.[30]

In the late 1920s a nation-wide appeal was launched to save Stonehenge from the encroachment of the modern buildings that had begun to rise around it.[31] By 1928 the land around the monument had been purchased with the appeal donations, and given to the National Trust to preserve. The buildings were removed (although the roads were not), and the land returned to agriculture. More recently the land has been part of a grassland reversion scheme, returning the surrounding fields to native chalk grassland.[32]

Neopaganism

10th Battalion, CEF marches past, winter 1914–15 (WW I); Background: Preservation work on stones, propped up by timbers

Throughout the 20th century, Stonehenge began to be revived as a place of religious significance, this time by adherents of Neopagan and New Age beliefs, particularly the Neo-druids. The historian Ronald Hutton would later remark that “it was a great, and potentially uncomfortable, irony that modern Druids had arrived at Stonehenge just as archaeologists were evicting the ancient Druids from it”.[33] The first such Neo-druidic group to make use of the megalithic monument was the Ancient Order of Druids, who performed a mass initiation ceremony there in August 1905, in which they admitted 259 new members into their organisation. This assembly was largely ridiculed in the press, who mocked the fact that the Neo-druids were dressed up in costumes consisting of white robes and fake beards.[34]

Between 1972 and 1984, Stonehenge was the site of the Stonehenge Free Festival. After the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985, this use of the site was stopped for several years and ritual use of Stonehenge is now heavily restricted.[35] Some Druids have arranged an assembling of monuments styled on Stonehenge in other parts of the world.[36]

Setting and access

As motorised traffic increased, the setting of the monument began to be affected by the proximity of the two roads on either side – the A344 to Shrewton on the north side, and the A303 to Winterbourne Stoke to the south. Plans to upgrade the A303 and close the A344 to restore the vista from the stones have been considered since the monument became a World Heritage Site. However, the controversy surrounding expensive re-routing of the roads has led to the scheme being cancelled on multiple occasions. On 6 December 2007, it was announced that extensive plans to build Stonehenge road tunnel under the landscape and create a permanent visitors’ centre had been cancelled.[37] On 13 May 2009, the government gave approval for a £25 million scheme to create a smaller visitors’ centre and close the A344, although this was dependent on funding and local authority planning consent.[38] On 20 January 2010 Wiltshire Council granted planning permission for a centre 2.4 km (1.5 miles) to the west and English Heritage confirmed that funds to build it would be available, supported by a £10m grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.[39] On 23 June 2013 the A344 was closed to begin the work of removing the section of road and grassing it over.[40][41]

When Stonehenge was first opened to the public it was possible to walk among and even climb on the stones, but the stones were roped off in 1977 as a result of serious erosion.[42] Visitors are no longer permitted to touch the stones, but are able to walk around the monument from a short distance away. English Heritage does, however, permit access during the summer and winter solstice, and the spring and autumn equinox. Additionally, visitors can make special bookings to access the stones throughout the year.[43]

The current access situation and the proximity of the two roads has drawn widespread criticism, highlighted by a 2006 National Geographic survey. In the survey of conditions at 94 leading World Heritage Sites, 400 conservation and tourism experts ranked Stonehenge 75th in the list of destinations, declaring it to be “in moderate trouble”.[44]

Archaeological research and restoration

{{{annotations}}}

Post-WW1 aerial photograph

17th century depiction of Stonehenge

Throughout recorded history Stonehenge and its surrounding monuments have attracted attention from antiquarians and archaeologists. John Aubrey was one of the first to examine the site with a scientific eye in 1666, and recorded in his plan of the monument the pits that now bear his name. William Stukeley continued Aubrey’s work in the early 18th century, but took an interest in the surrounding monuments as well, identifying (somewhat incorrectly) the Cursus and the Avenue. He also began the excavation of many of the barrows in the area, and it was his interpretation of the landscape that associated it with the Druids[45] Stukeley was so fascinated with Druids that he originally named Disc Barrows as Druids’ Barrows. The most accurate early plan of Stonehenge was that made by Bath architect John Wood in 1740.[46] His original annotated survey has recently been computer redrawn and published.[47] Importantly Wood’s plan was made before the collapse of the southwest trilithon, which fell in 1797 and was restored in 1958.

William Cunnington was the next to tackle the area in the early 19th century. He excavated some 24 barrows before digging in and around the stones and discovered charred wood, animal bones, pottery and urns. He also identified the hole in which the Slaughter Stone once stood. At the same time Richard Colt Hoare began his activities, excavating some 379 barrows on Salisbury Plain before working with Cunnington and William Coxe on some 200 in the area around the Stones. To alert future diggers to their work they were careful to leave initialled metal tokens in each barrow they opened. In 1877 Charles Darwin dabbled in archaeology at the stones, experimenting with the rate at which remains sink into the earth for his book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.

An early photograph of Stonehenge taken July 1877

The monument from a similar angle in 2008 showing the extent of reconstruction

William Gowland oversaw the first major restoration of the monument in 1901 which involved the straightening and concrete setting of sarsen stone number 56 which was in danger of falling. In straightening the stone he moved it about half a metre from its original position.[47] Gowland also took the opportunity to further excavate the monument in what was the most scientific dig to date, revealing more about the erection of the stones than the previous 100 years of work had done. During the 1920 restoration William Hawley, who had excavated nearby Old Sarum, excavated the base of six stones and the outer ditch. He also located a bottle of port in the Slaughter Stone socket left by Cunnington, helped to rediscover Aubrey’s pits inside the bank and located the concentric circular holes outside the Sarsen Circle called the Y and Z Holes.[48]

Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott and John F. S. Stone re-excavated much of Hawley’s work in the 1940s and 1950s, and discovered the carved axes and daggers on the Sarsen Stones. Atkinson’s work was instrumental in furthering the understanding of the three major phases of the monument’s construction.

In 1958 the stones were restored again, when three of the standing sarsens were re-erected and set in concrete bases. The last restoration was carried out in 1963 after stone 23 of the Sarsen Circle fell over. It was again re-erected, and the opportunity was taken to concrete three more stones. Later archaeologists, including Christopher Chippindale of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge and Brian Edwards of the University of the West of England, campaigned to give the public more knowledge of the various restorations and in 2004 English Heritage included pictures of the work in progress in its book Stonehenge: A History in Photographs.[49][50][51]

In 1966 and 1967, in advance of a new car park being built at the site, the area of land immediately northwest of the stones was excavated by Faith and Lance Vatcher. They discovered the Mesolithic postholes dating from between 7000 and 8000 BC, as well as a 10-metre (33 ft) length of a palisade ditch – a V-cut ditch into which timber posts had been inserted that remained there until they rotted away. Subsequent aerial archaeology suggests that this ditch runs from the west to the north of Stonehenge, near the avenue.[48]

Excavations were once again carried out in 1978 by Atkinson and John Evans during which they discovered the remains of the Stonehenge Archer in the outer ditch,[52] and in 1979 rescue archaeology was needed alongside the Heel Stone after a cable-laying ditch was mistakenly dug on the roadside, revealing a new stone hole next to the Heel Stone.

In the early 1980s Julian Richards led the Stonehenge Environs Project, a detailed study of the surrounding landscape. The project was able to successfully date such features as the Lesser Cursus, Coneybury henge and several other smaller features.

In 1993 the way that Stonehenge was presented to the public was called “a national disgrace” by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee. Part of English Heritage’s response to this criticism was to commission research to collate and bring together all the archaeological work conducted at the monument up to this date. This two-year research project resulted in the publication in 1995 of the monograph Stonehenge in its landscape, which was the first publication presenting the complex stratigraphy and the finds recovered from the site. It presented a rephasing of the monument.[53]

More recent excavations include a series of digs held between 2003 and 2008 known as the Stonehenge Riverside Project, led by Mike Parker Pearson. This project mainly investigated other monuments in the landscape and their relationship to the stones — notably Durrington Walls, where another ‘Avenue’ leading to the River Avon was discovered. The point where the Stonehenge Avenue meets the river was also excavated, and revealed a previously unknown circular area which probably housed four further stones, most likely as a marker for the starting point of the avenue. In April 2008 Professor Tim Darvill of the University of Bournemouth and Professor Geoff Wainwright of the Society of Antiquaries, began another dig inside the stone circle to retrieve dateable fragments of the original bluestone pillars. They were able to date the erection of some bluestones to 2300 BC,[2] although this may not reflect the earliest erection of stones at Stonehenge. They also discovered organic material from 7000 BC, which, along with the Mesolithic postholes, adds support for the site having been in use at least 4,000 years before Stonehenge was started. In August and September 2008, as part of the Riverside Project, Julian Richards and Mike Pitts excavated Aubrey Hole 7, removing the cremated remains from several Aubrey Holes that had been excavated by Hawley in the 1920s, and re-interred in 1935.[16] A licence for the removal of human remains at Stonehenge had been granted by the Ministry of Justice in May 2008, in accordance with the Statement on burial law and archaeology issued in May 2008. One of the conditions of the licence was that the remains should be reinterred within two years and that in the intervening period they should be kept safely, privately and decently.[54][55]

A new landscape investigation was conducted in April 2009. A shallow mound, rising to about 40 cm (16 inches) was identified between stones 54 (inner circle) and 10 (outer circle), clearly separated from the natural slope. It has not been dated but speculation that it represents careless backfilling following earlier excavations seems disproved by its representation in 18th- and 19th-century illustrations. Indeed, there is some evidence that, as an uncommon geological feature, it could have been deliberately incorporated into the monument at the outset.[14] A circular, shallow bank, little more than 10 cm (4 inches) high, was found between the Y and Z hole circles, with a further bank lying inside the “Z” circle. These are interpreted as the spread of spoil from the original Y and Z holes, or more speculatively as hedge banks from vegetation deliberately planted to screen the activities within.[14]

In July 2010, the Stonehenge New Landscapes Project discovered what appears to be a new henge less than 1 km (0.62 miles) away from the main site.[56]

On 26 November 2011, archaeologists from University of Birmingham announced the discovery of evidence of two huge pits positioned within the Stonehenge Cursus pathway, aligned in celestial position towards midsummer sunrise and sunset when viewed from the Heel Stone.[57][58] The new discovery is part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project which began in the summer of 2010.[59] The project uses non-invasive geophysical imaging technique to reveal and visually recreate the landscape. According to the team leader Professor Vince Gaffney, this discovery may provide a direct link between the rituals and astronomical events to activities within the Cursus at Stonehenge.[58]

On 18 December 2011, geologists from University of Leicester and the National Museum of Wales announced the discovery of the exact source of the rock used to create Stonehenge’s first stone circle. The researchers have identified the source as a 70-metre (230 ft) long rock outcrop called Craig Rhos-y-Felin (51°59′30.07″N 4°44′40.85″W), near Pont Saeson in north Pembrokeshire, located 220 kilometres (140 mi) from Stonehenge

Kultura amfor kulistych

Skocz do: nawigacji, wyszukiwania

obszar występowania kultury ceramiki sznurowej (ang. Corded Ware), kultura badeńska kolor fioletowy (ang. Baden) oraz kultura amfor kulistych (ang. Globular Amphora) III tys. p.n.e.

Kultura amfor kulistych to jedna z kultur neolitu, która występowała w latach 3100–2600 p.n.e. w dorzeczu Łaby, w Polsce, Mołdawii, na Wołyniu i Podolu.

Ceramika kultury amfor kulistych

(1/5)▶

Muzeum w Krasnymstawie

Muzeum w Krasnymstawie

Nazwa tej kultury pochodzi od charakterystycznego dla niej typu wyrobów ceramicznych o kulistym brzuścu. Ludność tej kultury eksploatowała krzemień pasiasty z kopalni w Krzemionkach Opatowskich. Na terenie Polski pozostawiła po sobie grobowce megalityczne typu skrzynkowego datowane na połowę III tysiąclecia p.n.e.

Spis treści

1 Osadnictwo

2 Zwyczaje pogrzebowe

3 Narzędzia

4 Zobacz też

5 Bibliografia

6 Linki zewnętrzne

Osadnictwo

Dotychczas odnalezione osady tej kultury charakteryzowały się małą ilością domów o konstrukcji słupowej zbudowanych na planie nieregularnego czworokąta. Czasami również w formie ziemianki.

Zwyczaje pogrzebowe

Groby najczęściej w formie skrzyń z kamieni, przykrytych ziemnym nasypem. Często dno grobowca oraz jego wierzchnia warstwa były brukowane. Wewnątrz znajdowano ozdoby, krzemienne narzędzia /siekierki/ oraz naczynia. Wiele pochówków zawiera również szczątki zwierząt, głównie bydła z obciętymi rogami. Na naczyniach zarówno na zewnątrz jak i wewnątrz umieszczano znak swastyki /Rębków Parcele wykopaliska w 1938 roku – dziś Rębków Borki/. W grobach znajdowano nawet sześć rodzajów garnków i naczyń glinianych co świadczy o różnorodnej diecie ówczesnych ludów. Ludy te wierzyły w życie pozagrobowe o czym świadczy wyposażanie zmarłych w narzędzia i naczynia /prawdopodobnie z jedzeniem/.

Narzędzia

Narzędzia to przede wszystkim krzemienne siekierki i krzemienne ostrza natomiast brak jest w znaleziskach kamiennych toporków. Garnki były wykonywane metodą doklejania uformowanych wstępnie wałków. Uszy na garnkach i naczyniach były niewielkie i służyły do zawieszania garnków na sznurkach. Brak w grobowcach naczyń które by odpowiadały dzisiejszym kubkom wynika prawdopodobnie z tego że były one wykonywane z mało trwałych materiałów np. ze skóry. Kształt szyjki garnków wskazuje na możliwość przykrywania ich właśnie skórzanymi kubkami. Ponieważ wiadomo, że umieszczany na garnkach znak swastyki był symbolem Słońca i Dobra oznacza to, że te znaki są pierwszymi znakami pisanymi na obecnych ziemiach polskich.

Zobacz też

kultura ceramiki wstęgowej rytej

kultura badeńska

kultura lendzielska

kultura pucharów lejkowatych

kultura ceramiki sznurowej

kultura pucharów dzwonowatych

Rodzaje budowli megalitycznych

Globular Amphora culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

Jump to: navigation, search

Approximate extent of the Corded Ware horizon with adjacent 3rd millennium cultures (after EIEC).

The Globular Amphora Culture (GAC), German Kugelamphoren-Kultur (KAK), ca. 3400–2800 BC, is an archaeological culture preceding the central area occupied by the Corded Ware culture. Somewhat to the south and west, it was bordered by the Baden culture. To the northeast was the Narva culture. It occupied much of the same area as the earlier Funnelbeaker culture. The name was coined by Gustaf Kossinna because of the characteristic pottery, globular-shaped pots with two to four handles. The Globular Amphora culture is thought to be of Indo-European origin and was succeeded by the Corded Ware culture.

1 Extent

2 Economy

3 Burials

4 Interpretation

5 Notes

6 Sources

Extent

Globular Amphora

It was located in the area defined by the Elbe catchment on the west and that of the Vistula on the east, extending southwards to the middle Dniester and eastwards to reach the Dnieper. West of the Elbe, some globular amphorae are found in megalithic graves. The GAC finds in the Steppe area are normally attributed to a rather late expansion between 2950-2350 cal. BC from a centre in Wolhynia and Podolia.

Economy

The economy was based on raising a variety of livestock, pigs particularly in its earlier phase, in distinction to the Funnelbeaker culture’s preference for cattle. Settlements are sparse, and these normally just contain small clusters pits. No convincing house-plans have yet been excavated. It is suggested that some of these settlements were not year-round, or may have been temporary.

Burials

Globular Amphora tomb

The GAC is primarily known from its burials. Inhumation was in a pit or cist. A variety of grave offerings were left, including animal parts (such as a pig’s jaw) or even whole animals, e.g., oxen. Grave gifts include the typical globular amphorae and stone axes. There are also cattle-burials, often in pairs, accompanied by grave gifts. There are also secondary burials in Megalithic graves.

Interpretation

The inclusion of animals in the grave is seen as an intrusive cultural element by Marija Gimbutas. The practice of suttee, hypotised by Gimbutas is also seen as a highly intrusive cultural element. The supporters of the Kurgan Hypothesis point to these distinctive burial practices and state this may represent one of the earliest migrations of Indo-Europeans into Central Europe. In this context and given its area of occupation, this culture has been claimed as the underlying culture of a Germanic-Baltic-Slavic continuum.[1]

Proto-Germanic

The Proto-Germanic stage can roughly be dated between 1800 BC and 250 BC, which approximately matches the dating of local Nordic Bronze Age culture (1800-500 BC) [The Trundholm sun chariot, the sun wheel sign, the petroglyphs depicting ships, bronze working, amber trade, burial mounds, etc]. On the other hand, the glottochronological evidence also tends to place the internal Proto-Germanic split in the second half of the first millennium BC. For instance, Toporova (2000) (based on Maurer and Schwartz) provides 500 BC as the date for the start of internal splitting in Proto-Germanic, whereas Starostin & Burlak (2001) date it to circa 100 BC (however the latter Starostin’s nonlogarithmic glottochronology seems to yield incorrect dates).

The Proto-Celtic migration

The Celtic languages are shown as several distinct groups because of the remarkable and obvious differences between Gaulish, Brythonic, and Goidelic branches. Basically, it is not correct to consider them all as “just Celtic”, since these are in fact very lexicostatistically different (sub)groups with an early temporal separation. Also, note that we know very little of Lusitanian, Celtiberian and other obscure early representatives of the Celtic cluster, so their exact position within the Celtic branch is still questionable. (A possible inclusion of Proto-Albanian as either part of or close to “Celtic” has also been considered separately as a plausible hypothesis, see here).